In 1940 Roy Dalgarno was living on Bedarra Island, near Tully, Qld, as a guest of fellow artist Noel Wood. They held an exhibition of their work in Brisbane at the end of the year. (Courier-Mail, 6 December 1940)

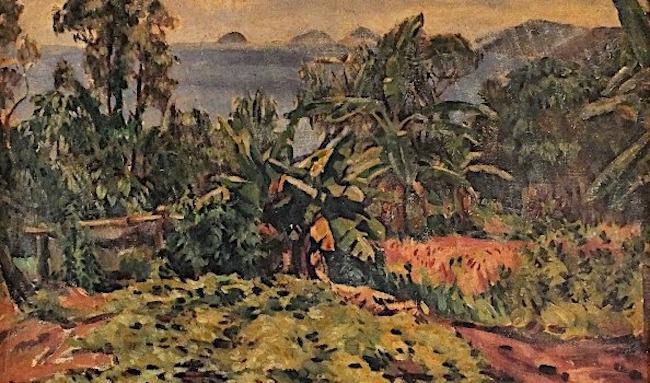

Landscape by Roy Dalgarno thought to have been painted while he was living on Bedarra Island, in 1940. (Collection: Lynn Dalgarno)

Tropical landscape by Dalgarno, c. 1940 (City of Townsville Art Collection)

Dalgarno’s “Aboriginal stockman”, n.d., is typical of his portraits of the 1940s. (Collection: Lynn Dalgarno)

Cairns, in c. 1939. (C. B. [Clem] Christesen, Queensland Journey, Queensland Government Tourist Bureau, n.d. [c. 1939], p. 111.) Clem Christesen established the literary magazine Meanjin Papers in 1940.

It’s after sunset on the Esplanade. Roy’s wondering, what next. What’s it all to do with me? I came North for peace and quiet, also painting, also to be on my own to think, now that it’s all over with Nadine. I’m just a man. A scribbler with some chalk and paint. Best return to where it’s safe, where I can live offshore, on Noel’s island, beside the beach, as harmless as a pair of mutton-birds. [RED, page 146]

“The Sweet Potato Patch, Bedarra Island” by Noel Wood, 1937. (Private collection)

Dalgarno met Noel Wood in c. 1930 when they were art students in Melbourne. In 1940 Noel invited Roy to Bedarra Island, where he was living a self-sufficient existence while painting in a brightly coloured “tropical” style. Photographs in the Cairns Post (1 January 1939) show Noel in a sarong climbing a coconut tree. Dalgarno and Wood “built a studio of plaited palm leaves” and produced all their own food (Cairns Post 5 December 1940). The island had no jetty, Dalgarno explains, “so we jumped over the side with our supplies and waded ashore.” (Roy Dalgarno, The Winking of an Eye [unpublished autobiography], Section 9, p. 16)

In Noel’s words, “I am not an escapist. I have worked out satisfactorily how I can live happily in this mad world without worrying anyone.” (Courier-Mail, 07 September 1940, p. 7)

Six months later, Security forced Roy to leave Bedarra. He and Noel had just completed their successful joint exhibition of “Tropical Paintings” in December 1940. Roy gives an account of the break-up in his autobiography:

When I arrived at Tully, Noel met me at the station. He’d been back about a month and I could see immediately that some problem had come up.

. “Look Roy, I’ve got some bad news. I’ve been told by the police not to allow you back on the island.” I couldn’t believe this. …

. The intelligence people had instructed Tully Police Chief, Sergeant Schmidt, not to allow me back on the island. Noel explained to me if I kept on living on Bedarra they would close him up; they wouldn’t allow him to live there even, because they said it’s a sensitive security issue. They’d apparently planned on building some sort of military establishment there and they considered me a security risk. A security risk? Because I was a Communist or a member of the Left Book Club. I was confused and devastated to have my island life terminated. All I thought to say was, “Jesus Christ, what am I to do now?”

. Noel of course was terribly embarrassed. He couldn’t stand to have his idyllic life disrupted. After a while I appreciated his situation there. I understood that it was an awkward decision for him to make on the spur of the moment, but he was faced with a fait accompli by Sergeant Schmidt. He managed to remain there during the war and wasn’t called up for service as they normally would have. He decided to grow tomatoes there for the war effort and was allowed to stay. Noel, being a very conservative chap, … [was adamant about] protecting his Shangri-La from publicity.

. I don’t know how we got on so well together ….

. I never saw Noel after that. We never corresponded, although I had left my art books and many personal things, some preliminary sketches, and clothes, on Bedarra island. I was so disgusted and depressed about the whole affair and returned to Brisbane that same evening after a few farewell drinks at the Tully pub, but it was a most uncomfortable farewell for both of us. I wasn’t even permitted on the island to collect my things. He may have been unfit for military service even—I never knew. We hadn’t fallen out in any way. He was clearly pressurised. Noel was completely apolitical so it would not have occurred to him to take a political stand.

. So much for the Garden of Eden. …

(From Dalgarno’s autobiography, Section 10, pp. 9–10. A similar account is in “Interview with Roy Dalgarno, artist [sound recording] / interviewer, Barbara Blackman”, 1984, Bib ID 1078676, National Library of Australia.)

Soon after this episode Dalgarno joined the Camouflage unit of the RAAF, working in far north locations, including some of the islands of north Queensland, until the end of the war. This is the period of a later episode in RED, starting on p. 261.

•

Jean Devanny and Ralph Gibson, influential communist writers at this time, also appear in this episode:

Cover of the first edition of Sugar Heaven (1936)

Jean Devanny, born in New Zealand, lived in north Queensland from the mid-1930s. She wrote a number of novels. The best known is Sugar Heaven (1936), which deals with the blight of Weil’s disease among the cane cutters.

Jean Devanny with cane workers, Mourilyan, 1935, when two thousand cane cutters across north Queensland (most of them from Italy and Yugoslavia) and mill hands (mostly Anglo/Celtic) united to strike for two months. Their claim was that, to prevent further outbreaks of Weil’s disease, the cane should be burnt before it was cut.

•

Ralph Gibson persuaded Dalgarno to join the Communist Party when they were both living in Melbourne. So he is surprised to see his old friend turn up in far north Queensland:

It’s Ralph Gibson. Isn’t he supposed to be in Melbourne? Coming straight towards him, here, in the tropic sunlight, like a heat-delusion. [RED, page 145]

As early as 1931-32, Gibson believed that the Depression “was the last crisis, and we would therefore be facing early revolutionary battles”. “We felt that the revolution might be near and that there was a huge amount of work to be done if we were to be ready in time.” (Ralph Gibson, The People Stand Up, self-published, 1983, pp. 49, 33)

In 1937, at a peace rally at the Savoy Theatre in Sydney, Madeline Wood was impressed by a speech of Ralph Gibson’s. The event was crowded, with many standing at the back of the theatre and it “was the best Peace Meeting I have been to … . But the speech of the evening was given by Mr Ralph Gibson, … [a] representative of the Melbourne Branch of the Movement Against War and Fascism.” (Madeline Wood, letter to Fred Wood, 7 February 1937, “Wood family papers, with papers of the Whitfeld family, 1833-1985” (ML MSS 2077), Mitchell Library, Sydney)

Ralph Gibson in c. 1936 (left) and a poster for a talk he gave with Vance Palmer in 1936 (right)

A prolific speaker and pamphleteer, Ralph Gibson did something rare among communist writers—he imagined in some detail what Australia would look like “five years” after a socialist revolution. In a booklet that was expanded and revised several times, Gibson takes the reader for a walk around the city and suburbs of Melbourne as he thought they would be under socialism.

1937 edition (left) and 1951 edition (right)

First published in 1937 as a 16-page pamphlet, Gibson’s Socialist Melbourne was expanded and much revised in 1951. Here he is visiting a new socialist factory:

To go inside the factory was a new and wonderful experience. One felt as if one had walked into a club rather than a factory. Many of the workers seemed able to leave their jobs and talk to you when they wanted to. They showed you their factory-newspaper hung on the walls of the factory; and there, in the full light of day, one could question the manager and the way in which he managed the factory. (1937 edition, p. 1)

At this moment the whistle goes for lunch. We follow the workers into a fine large dining room, in which excellent three course meals are served at cost price. We are used to surprises now, and don’t flicker an eyelid when we see next to the dining room a surgery and first aid station with doctor and nurse on the spot ready to treat any sick or injured worker free of charge. … Gradually it comes home to us. This is a workers’ factory, part of a workers’ society. We see this even more clearly when the workers come streaming into the room after lunch. … The factory, we find, has developed new functions. Through its elected committee the worker obtains his sick, accident, holiday and other benefits under the State insurance scheme. This factory even has its own rest home. … The workers have compiled a splendid library. They come together in sporting, dramatic and other groups in their hours of leisure. In short, the factory, under its own elected committee, has become a real centre of social and cultural life as well as a workplace.” (1951 edition, pp. 7–8)

•

One last note about Gibson’s father and brother:

If he looks again, will the man be Ralph—or will he change into a stranger? Like they teach you in philosophy, like Ralph himself would say to Roy, teaching him how philosophers talk, philosophers like Ralph’s father. How can you be sure? [RED, page 145]

Ralph’s father, W. R. Boyce Gibson, was professor of philosophy at Melbourne University until his death in 1935; his ideas were influenced by Christian ethics and German idealism. Ralph’s brother, Alexander Boyce Gibson, who took his father’s place as professor in 1935, favoured Plato, Descartes and the European philosophical tradition to the British linguistic philosophy of the 1930s, which was also taught in the same department. Both professors emphasised personal idealism and the “mental world”. In contrast, Ralph’s ideas were founded on the material world, Marx and social responsibility.